The “Bloody Code”: Crimes and their Punishments in the 18th Century

Photo by Caryn Sandoval on Unsplash

Crimes and their punishments were often utterly bizarre in England until well into the 19th century and were extremely unequal and unfair.

The British Legal System in the 17th Century

In the 17th century there was a belief that crime was increasing, particularly property crime, leading the wealthy ruling classes to enact more laws to protect their possessions. The economic shifts from the agricultural and industrial revolutions were seen as a threat to property, which led to more stringent laws.

What was the “Bloody Code”?

The Waltham Black Act of 1723 was a British parliamentary act that significantly expanded the number of capital crimes, making it the foundation of the "Bloody Code". The Act was a response to civil unrest and organized poaching, particularly by groups of men who blackened their faces for camouflage. It made over fifty offenses capital, including poaching deer in royal forests, damaging property like orchards and gardens, and even carrying hunting traps or keeping dogs suitable for poaching.

The name "Bloody Code" was given later by critics of the harsh system, which aimed to deter crime, in particular property crime, through severe punishments. The Waltham Black Act was expanded over the years and greatly strengthened the criminal law by specifying over 200 capital crimes, many with intensified punishment, by the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

Crimes could have vastly different punishments depending on the property stolen or the circumstances of the crime. For example pickpocketing carried the death penalty, but child stealing was not even an offence. To break a pane of glass at 5 p.m. on a winter's evening with intent to steal was a capital offence; to break into a house at 4 a.m. in the summer when it was light was only a misdemeanour. To steal goods from a shop and to be seen to do so was worthy of transportation; to steal the same goods without being observed, was punishable by death.

What was “Pious Perjury”?

To avoid the death penalty for minor crimes, juries would sometimes resort to "pious perjury”. So severe were the laws that many jurors ended up deliberately under-valuing stolen goods so as to avoid inflicting the death sentence on the accused. Unsurprisingly the death penalty was often avoided by the Courts as the unfairness of the Law was evident to all. It was becoming clear that dealing with an unmarried mother concealing a stillborn child and someone else destroying a fish pond were scarcely comparable actions and neither worthy of the death penalty.

The Rise of Penal Transportation

In 1785, Australia was considered to be a suitable place to which to transport convicts and it’s estimated that over one third of all criminals convicted between 1788 and 1867 were sent there.

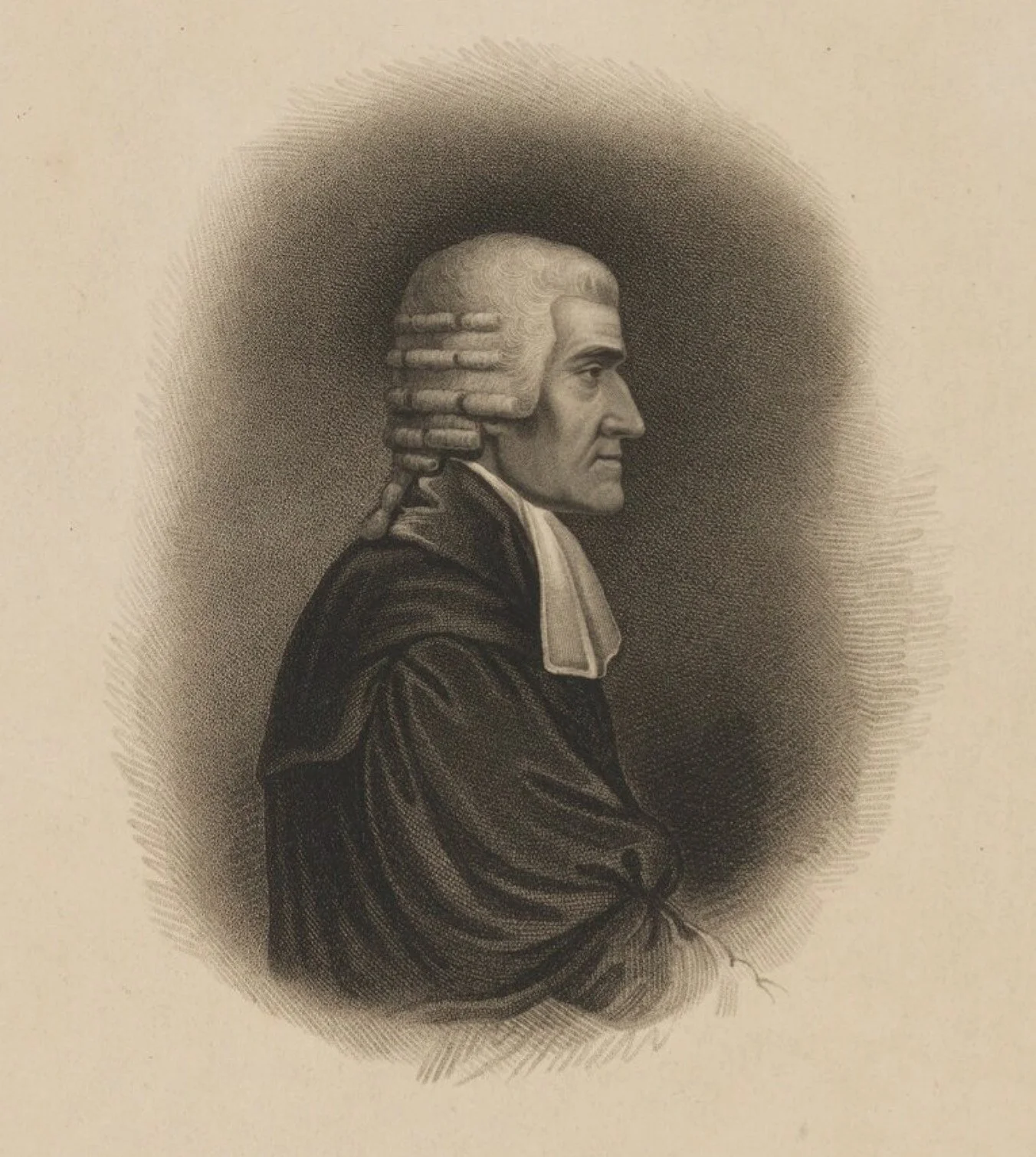

Sir Samuel Romilly. By engraving by John Kennerley, published by Zachariah Sweet, after Charles (Cantelowe, Cantlo) Bestland - https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw202128/Sir-Samuel-Romilly, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=152099560

In 1808, after much campaigning, social reformer Sir Samuel Romilly succeeded in repealing the death penalty for some minor crimes, and as the century progressed transportation became a more popular mode of punishment.

The Rise of Social Reform

Social reformers and a growing public opinion recognized the injustice and cruelty of the system, leading to calls for criminal law reform in the early 19th century.

By 1823 the Judgment of Death Act made the death penalty discretionary for most crimes and by 1861 the number of capital offences had been reduced to five. The last execution in the United Kingdom took place in 1964, and the death penalty was abolished for various crimes in the following years., most recently for Piracy with violence, Treason and six military offences in 1998.

Reintroduction of the death penalty under any circumstances was prohibited by treaty (Protocol 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights) in 2004.